For years, tariffs have been marketed in American politics as a tool of economic patriotism—a way to protect domestic industries, pressure foreign competitors, and restore balance to global trade. But as President Donald Trump once again places sweeping tariffs at the center of his economic platform, economists warn that the plan may function less as a strategic policy lever and more as a giant national sales tax—one that risks slowing U.S. growth, raising costs for households, and sowing long-term structural inefficiencies.

The Pitch: Tariffs as Leverage

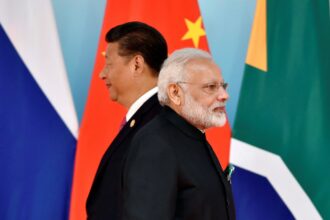

Trump has long argued that tariffs serve as a weapon against unfair trade practices, particularly from China. His proposal, which includes the possibility of imposing a 10% tariff on all imports and higher levies on Chinese goods, is pitched as a way to level the playing field and “bring jobs back to America.”

In campaign speeches, Trump frames tariffs as forcing foreign producers to pay for access to the American consumer market—revenue, he argues, that will flow into federal coffers rather than into Beijing’s.

The Reality: Consumers Pay the Bill

But economists across the political spectrum have repeatedly shown that tariffs are paid, not by foreign producers, but largely by domestic businesses and consumers. Importers pass higher costs along the supply chain, and retailers ultimately embed them into the prices of everyday goods.

“The effect is indistinguishable from a broad-based consumption tax,” said Wendy Edelberg, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution. “You can call it a tariff, but at the checkout line it’s a sales tax—just one that happens to be hidden from view.”

According to a Peterson Institute for International Economics study, tariffs implemented during Trump’s first term cost the average U.S. household between $500 and $1,000 annually through higher prices on goods ranging from washing machines to canned soup. A blanket 10% tariff, economists estimate, could double or triple that burden.

The Growth Drag

Beyond household budgets, tariffs risk acting as a brake on broader economic growth. A blanket national tariff raises costs for manufacturers who rely on imported inputs, from semiconductors to steel. That erodes competitiveness, squeezes margins, and often leads to fewer jobs in precisely the sectors tariffs are intended to protect.

The Congressional Budget Office has modeled that a broad-based tariff could shave up to 0.5% from GDP growth annually, depending on its scope and duration. That translates into billions of dollars in lost output and weaker long-term investment.

A Regressive Tax Structure

Perhaps most striking is the regressive nature of tariffs. Because lower- and middle-income households spend a greater share of their income on goods rather than services, they shoulder a disproportionate share of tariff-induced price increases.

“Tariffs operate like a flat sales tax on everything imported, from food to clothing to electronics,” said Jason Furman, former chair of the Council of Economic Advisers. “That’s the very definition of regressive.”

In effect, a 10% tariff would weigh most heavily on families already struggling with high living costs—a political irony given that such households form a core constituency of Trump’s base.

Geopolitical Risk and Retaliation

Global partners are unlikely to accept blanket tariffs quietly. China, the EU, and Canada all retaliated against Trump’s first-term tariffs with levies of their own, targeting U.S. agriculture and manufacturing exports. A broader tariff regime would almost certainly provoke a new round of retaliation, potentially closing off foreign markets to American farmers and industrial producers.

Trade wars, once unleashed, rarely end neatly. They risk fracturing supply chains, discouraging foreign investment, and undermining America’s leadership in global trade architecture.

The Hidden Taxation Narrative

The heart of the issue is political transparency. While no U.S. administration could hope to pass a new national sales tax through Congress, tariffs function as a stealth equivalent. Unlike income taxes, which are highly visible, tariffs are buried in consumer prices—diffused across millions of transactions, paid silently by households every time they shop.

“It’s taxation without the honesty of admitting it,” said Paul Donovan, chief economist at UBS. “You can call it populism, you can call it trade protection, but at the end of the day it’s a national sales tax by another name.”

The Long-Term Consequences

Over time, sustained reliance on tariffs risks distorting the U.S. economy in several ways:

- Less efficient allocation of capital, as companies adjust supply chains based on tariff barriers rather than productivity.

- Erosion of global competitiveness, as higher input costs weaken U.S. exporters.

- Inflationary persistence, as tariffs keep consumer prices elevated even as monetary policy seeks to cool inflation.

- Weakened alliances, as trade disputes spill into diplomatic rifts.

While tariffs may deliver short-term revenue and political soundbites, their longer-term cost is an economy burdened by inefficiency, inflation, and strategic isolation.

Conclusion: The Price of “Scapegoat Economics”

Trump’s return to tariff-heavy economics highlights a broader trend of weaponizing trade policy for domestic politics. Yet economists stress that the rhetoric obscures a simple truth: tariffs are taxes, borne overwhelmingly by U.S. households and businesses, with real consequences for growth.

As the debate intensifies ahead of 2025, investors and voters alike face a pivotal question: is America prepared to accept slower growth and higher consumer costs for the symbolism of tariffs—or will the nation recognize them for what they are, a giant national sales tax dressed in the language of economic nationalism?